Herbie Hancock played at the Hollywood Bowl last night. It was a special show that was commemorating Herbie’s “Headhunters” album, which was one of many milestone albums for him. For many reasons, I wasn’t able to go to the show, but Herbie was on my mind, and that led me to think about Miles Davis, and his mentoring of what might be considered to be a group of the greatest musicians of the twentieth century.

I’ve been very fortunate to spend a substantial amount of time with Herbie over the years, and have had the opportunity to speak to him, and more importantly, to listen to him talk about various albums that he made while playing with Miles.

1965 was an interesting year in the context of Miles and his quintet. He had finally arrived on the right combination of players when, at Tony Williams’ urging, he hired Wayne Shorter away from Art Blakey’s band. According to Wayne, who I also have had the opportunity to speak to about this juncture, almost immediately Miles decided that he wanted to make a record with the new quintet of Wayne, Herbie, Tony Williams and Ron Carter. At an early juncture after Wayne joined the group, Miles called Wayne and told him to be at the studio the next day. The way that Wayne told me the story was (loosely quoting from memory), “I used to have a little briefcase that I carried music that I was working on in. You know, one of those brown ones with latches?…When Miles called to tell me to be at the studio he paused at the end of the conversation and said “…… and bring the briefcase!” I have to pause here to say that every time Wayne would tell me stories about Miles, his imitation, which was flawless, never failed to elicit convulsive laughter from me. These sessions were to end up forming Miles’ album E.S.P.

A relatively short amount of time later the band was booked to play 2 nights at a jazz club in Chicago called The Plugged Nickel. According to Herbie, on the way to the club, Tony, who was quite often the instigator of things in the combination of the personalities of the group, suggested that they should “not play any of the shit that we knew that worked during the gigs there, so we all took an oath to do this.” In other words, he felt that the group had fallen into musical ideas and arrangement artifacts that were guaranteed to “work”, pleasing the audience and apparently pleasing Miles.

As they drove up to the club, Herbie said that they saw the recording truck outside of the club, and looked at each other, with the implication being “so are we going to still hold to the oath?” They all decided that they would follow through, and approach playing everything without any of the artifacts that they had fallen into using.

The songs that Miles was calling was still relying heavily on standards, with a few of the new songs that were to appear on E.S.P. I remember when I first heard the Japanese pressing of “Live At The Plugged Nickel” vividly. I was absolutely floored. It was an entirely new way of playing jazz. Nothing was literal. Everything was metaphor. I ended up then having a cassette of the album, which never left the player in my car for a month.

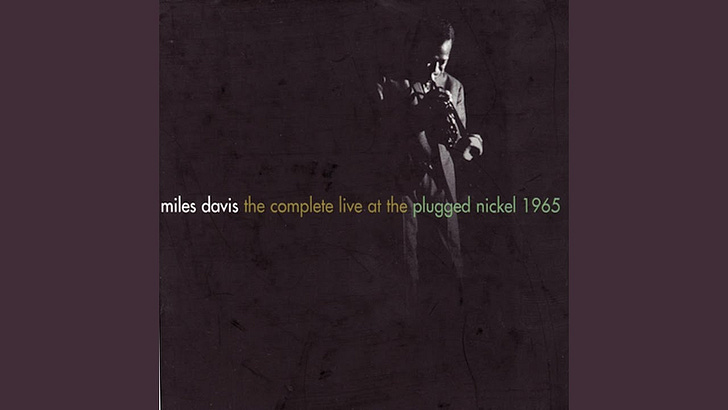

Years later, a boxed set of “The Complete Miles Davis Live At The Plugged Nickel” was released by Columbia. It contained every set from the group’s engagement at the club. Listening to this boxed set in it’s entirety just confirmed my feeling that this was some sort of pinnacle that they had reached. It was like James Joyce transmuted into a musical form. Nothing literal, all suggestion and contrasting implied fragments.

According to Herbie, they all expected Miles to react negatively to approaching the music this way, but to their surprise, he approved of it (in other words he didn’t say anything). This doesn’t surprise me, as I think that Miles always wanted to break fresh ground in how he approached music. Whenever people ask me the question “who do you think was the greatest producers of the 20th century, I almost always answer “Miles Davis” (once in a while I say Miles and George Martin!)

The way that the quintet approached the music on the Plugged Nickel renditions of these songs that they were playing, completely changed the way that I thought about music, and what was possible with instrumental music.

Years later, when I was beginning to work on selecting the songs that we would include on what became “River: The Joni Letters”, I brought the music and lyrics to about 25 of Joni’s songs over to Herbie’s house, and sat down with him in his studio. Before I put the first song on he said “you know…. I’ve never listened to words in songs!” I responded by laughing, and saying “Well, Herbie…. you’re going to have to start now!” and we both laughed.

In retrospect, I think that he actually had been listening to the words of standards by osmosis, as Miles obviously listened closely to the lyrics to all of the songs that he played, and approached those well-worn songs with an illustrative and painterly approach.

All of the members of that great group ended up changing the whole way that one could approach music on that instrument. It’s very rare, in the world that we live in, where most jazz is learned in schools, to hear the kind of playing that resulted from the context that Miles created, and what he brought out in those incredible musicians. On The Plugged Nickel material there is no “trying to impress” or anything remotely resembling it. It’s all literature and metaphor.

Great insights.